Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand

January 24 - February 8, 2024

Mike and Judy Henderson

I graduated in 1968 from LSU with a degree in Electrical Engineering. I had my cap and gown on when I went to the mailbox, and there was a letter from the selective service board re-classifying me to 1A. Great graduation gift.

Shortly after graduation, I headed west in my 1962 Volkswagen towards

California where I had a job waiting for me at

Pacific Missile Test Facility at

Pt. Mugu (very close to

Oxnard, CA). I went northwest and caught

Route 66, which

I followed to California.

Interstate 10 didn’t exist back then.

California was a wonderful place. The air was cool, there were a lot of

things to do, and I met a good group

of people at the apartment I was living in. And the job was interesting. I was

working on the microwave system that was used to carry data and voice across the

missile range.

But Uncle Sam had not forgotten me, and I eventually received my induction

notice. A friend who had served in the military told me that it was better to be

an officer than an enlisted man, so I applied for

Officer Candidate School, and

was accepted.

I delayed my induction by requesting that it be moved from Louisiana to

Southern California but that was just to delay things. I had to go back to

Louisiana for a variety of reasons. On Monday, November 18, 1968, I went to the

Customs House on Canal Street in New Orleans and was sworn into the US Army. I had a two-year

obligation. (I know some of these dates because they’re on my

DD-214).

There were three of us sworn in that day, and we were given bus tickets to

Ft. Polk, LA

(recently renamed to Ft. Johnson) , which is near

Leesville, LA, about 250 miles from New Orleans.

I won’t bore you with tales of

basic training – it was fairly straight

forward. I became the trainee company commander, which gave me some perks, such

as not having to pull

KP (Kitchen

Police).

But it also came with some headaches. One cold day the company was marching

with rifles and packs, and I was in the front, sweating despite the cold. At the

back of the company was a pickup truck driven by one of the trainees. I thought

to myself, “That guy is the smart one” and decided that I’d become a driver in

my next training assignment, which was Advanced Infantry Training (AIT), also at

Ft. Polk.

Pt. Mugu, where I had worked in California, was a Navy base and if you

wanted to drive on the base, you had to have a military driver’s license, which

I had obtained.

In one of the first formations at AIT, the sergeant asked if anyone had a

military driver’s license, and I practically ran over people to volunteer. They

sent me and a couple of other people for a driving test, driving a

two-and-a-half-ton truck, known as deuce and half. It was diesel and stick shift,

but that was no problem for me. I had never owned a car with an automatic

transmission so driving it was easy for me. Here's what deuce and a half

looked like.

As a side note, military vehicles do not have keys - just a switch to turn on the electrical, and a button to start the engine. You don't want to have to go looking for a key in war time. Unfortunately, that made military vehicles easy to steal in Saigon - we had to use a lock and chain on the steering wheel.

For all of AIT, I was a driver. And drivers did not have to pull KP. On days that I was to drive, someone would wake me a half hour early and I’d go get a truck from the motor pool and park it at the company. Then get breakfast. By then the company was ready to move out and they boarded the truck, which I drove to the training site. I’d take part in the training.

The training was not difficult. The Army was just trying to teach us things

– they weren’t trying to make our lives miserable. I was good with a rifle – I

had used a .22 since I was young and could shoot well. I qualified “Expert” with

the M16.

Here's a Polaroid picture of me in either Basic or AIT. It looks like cold weather which might indicate Basic training. I don't remember the other guy's name.

At the end of AIT, I was to go to OCS but there was a wait before the next OCS class started. I was sent to a “holding company” where I drove jeeps carrying various officers to training sites. On one occasion, I was on a two-day field assignment. At the end of the first day, as it was getting dark, I went back to the camp site for the cadre people (not the trainee area) and filled up the jeep from a fuel tanker parked there. As I drove away, the jeep engine started running very rough and the exhaust was white smoke. I found that I could keep it running if I pulled the choke out about halfway. I went back to the fuel area and realized that I had filled the jeep with diesel, not gas.

I drove the jeep around for an hour or so, to burn off some of the fuel.

Then I went back and filled it with gas. It still smoked and I had to leave the

choke out part way, but it ran, and I used it the next day. That evening, I

turned it into the motor pool and didn’t say a word to the people there.

Eventually, I got orders for OCS at

Ft. Benning, GA

(Fort Benning was renamed recently to

Fort Moore). OCS was different from

basic and AIT. There was a lot of harassment in OCS. I suppose what they were

trying to do was to put the “candidates” under stress to see how they responded.

A lot of it was similar to the harassment that first year (plebe) students

endure at West Point.

In my opinion, it was mainly counter-productive. It’s difficult to learn

when you haven’t had enough sleep and are harassed at every opportunity.

We lost about a third of the candidates. Some quit and some were kicked out.

I felt really bad for the ones kicked out. They went back to being an enlisted

man and almost certainly were sent to Vietnam as a “grunt” (infantry). Most were

college graduates and could have contributed in more meaningful ways.

I have a few stories about OCS. A friend of mine was Jewish. He suggested to

me that I sign out of the company on Friday evenings with him to go to

synagogue. Of course, we didn’t go to synagogue – we went to a bar.

Then on Sunday, I’d sign out for Christian services, and didn’t go to church

either. It was just a way to get away from the company and the harassment.

One day, one of the tac (short for “tactical”) officers called me into his

office and said, “Henderson, what is this shit? You’re signing out for Jewish

services on Friday and Christian services on Sunday.” I looked straight at him

and replied, “Sir, I’m thinking of converting.” That set him back and he started

asking me questions about what we did at synagogue. Of course, I had no idea

what went on at synagogue, so I had to make up a few things. Luckily, he had no

idea what went on at synagogue either. If he had asked me where the synagogue

was, I’d have been dead – I had no clue.

But after that I quit signing out for Friday Jewish services.

One training class was “Land Navigation” where you’d use a compass and

topographic map to navigate a course on a training field. The field was either

woods or high grass. The training required you to navigate a course on the field

which would lead you to a post with a letter or number on it. Then you’d

navigate another course to another post, etc. The last course would take you back to the starting point. You’d

enter the letter or number of the posts you had found on each leg on your card

and that way the instructor would know if you had done the course correctly.

For many of us this was easy. So, after the first or second land navigation

class, we’d head out into the field, find a tree, and go to sleep. Then we’d

just mark our card with anything. The instructors thought we were hopeless.

Towards the end of OCS, I learned that I could put in a request for a branch

transfer (a branch is something like Infantry, Artillery, Armor, etc.). Since I

had my EE degree and experience in electronics, I requested a transfer to the

Signal Corps. I didn’t have a lot of hope, but it was worth a try. At the end of

OCS, surprise, surprise, I was granted a branch transfer into the Signal Corps.

Not only that, but they asked for other people to apply for a branch transfer to

the Signal Corps. They had shut down the Signal Corps OCS and didn’t have enough

Signal Corps lieutenants.

Think about this for a minute. If you stay in the Infantry, you’re going to

be sent to Vietnam as a platoon leader in the field. You’re almost certain to be

shot at, and some (small) percent of the platoon leaders are going to be killed. In the

Signal Corps, you might not get sent to Vietnam, and if you did go, you wouldn’t

be out in the brush carrying a rifle. A transfer to the Signal Corps was a

possible lifesaving event.

I helped several of my friends write their application for a branch

transfer. I asked them for any radio or communications experience they might

have had, and I expanded upon that (quite a bit). I think all their applications

were approved and they were commissioned into the Signal Corps. I’m glad I was

able to help them.

Eventually, graduation day, Wednesday, October 29, 1969, came around and we

were commissioned as second lieutenants. We had a two-year obligation from the

date of our commissioning. I had been in the Army almost a year at graduation,

so I was going to spend three years in the Army. But I was a Signal Corps

officer which would make my life much better, and safer, than if I had stayed an

enlisted man.

Next the Army sent me to Signal Officer’s Basic Course at

Fort

Gordon in Augusta GA (Fort Gordon was renamed recently to

Fort Eisenhower). I

don’t remember how long that course was, but life was much better and easier as

an officer than it had been as an enlisted man.

Back then, Army communications were primitive (by today’s standards) but it

was interesting to learn about it. The only real story I have about that course

occurred at the end of the course. While I don’t have any records as to the

dates, it must have been about January or February 1970. It was cold.

The last event of the training course was a field maneuver where we’d go out into the field for a few days and set up, and operate, communications. The evening before the maneuver, we gathered in a theater at the base and the commanding general addressed us.

If it had been an Infantry

maneuver, the general would have said something like, “Men, you have a unique

opportunity to experience field maneuvers in cold weather. This doesn’t happen

for each class so you should be thankful for this opportunity.”

No, that’s not what the

general said. He said, “Men, it’s too cold and I’m cancelling the field

maneuver.” Love the Signal Corps.

At the completion of Signal

Officer Basic Course, I was assigned to a

tropospheric scatter company at

Ft.

Riley, KS. I was quite excited by this assignment - tropospheric scatter was a

microwave communication technology and would be valuable to learn. It could lead

to civilian jobs after my military service.

I had some leave, which I

spent with my family, and then headed to Ft. Riley. Was I disappointed when I

arrived. The company I was assigned to did not have any equipment – I was told

it had all been sent to Vietnam. But we had a full complement of officers and

enlisted men. It was commanded by a captain, with four lieutenants as platoon

leaders, and probably one hundred enlisted men.

The enlisted men had all been

trained, and were highly qualified, on the tropospheric scatter equipment, but

since there was no equipment, they were used for “utility detail” assignments,

such as cutting grass and picking up trash.

There was nothing for the

lieutenants to do. The first sergeant would get the assignments for the company,

and the non-commissioned officers (such as E-5 sergeants) would supervise the

work. I, and the other lieutenants, were just left at the company office to sit

around all day. For me, it was agony.

I would occasionally check

out a .45 pistol and some ammunition and go to the pistol range to shoot. The

captain understood and tried to keep us busy. He sent me to CBR school

(Chemical, Biological, and Radiological). That was an interesting class. We

learned how to make napalm and a bit about explosives. But the class was only

about a week long.

After work, I found the craft

shop and did woodworking and some ceramics work. I can understand how some of

the officers became alcoholics – they went to the Officers Club and killed time

by drinking.

One day, the captain said to

me, “I have to give a re-up speech to Jones. I don’t know what I can say to

him.” (Re-up means to re-enlist to stay in the Army. I doubt if many of the

enlisted people re-up’ed from our company.)

I had about a year and a half

to go on my obligation, and I knew I couldn’t survive the boredom at Ft. Riley.

But my alternatives were few. There was no way the Army was going to transfer me

to an active unit – there just weren’t many of them, and I had no special claim

on a spot. The only place I could volunteer for was Vietnam.

So that’s what I did.

You might think that’s crazy,

but I figured that being in the Signal Corps would protect me. As a Signal Corps

lieutenant I wouldn’t be out beating the bush with a company of Infantry

soldiers – I’d be at some base handling communications.

My request was accepted, and

I received orders for Vietnam about early May, 1970. I had some leave coming,

which I spent with my family in Louisiana. I reported to the

Oakland Army Depot

sometime around the end of May. We had about five days of classes about Vietnam,

at the end of which we were transported to

Travis Air Force base where we

boarded a chartered

Boeing 707.

We flew first to a civilian airport in Alaska – don’t know which one, maybe Anchorage – where we refueled. There was snow still on the ground. Then we flew to an airbase in Japan for another refueling. From there it was to Biên Hòa, Vietnam, where we arrived about 3am on July 2, 1970.

When we got off the plane, we were loaded into

military buses with wire mesh over the windows (to block hand grenades). There

was a jeep with an

M-60 machine gun on a pedestal who led the convoy to

Long Bình, where we’d billet for the night.

I don’t remember a lot about Long Bình – I wasn’t

there long, maybe two days, and then I was sent to

Saigon where I received my

orders, and was issued jungle fatigues and other Vietnam stuff.

My orders were to report to a certain major where I

would be an advisor to a

Vietnamese Regional Forces/Popular Forces group

(abbreviated RF/PF and called “Rough Puffs”). I supposed the assignments people

recognized that I had gone through Basic, AIT, and Infantry OCS so they figured

I could function as an advisor to the Rough Puffs.

We had good telephone

communications in Vietnam, so I called the major to ask how to get to him. I

told him I was new in country and had been assigned to his outfit but didn’t

know how to get to him.

We talked a bit and then

the major asked me, “What branch are you?”

I was a bit confused by

that question and replied, “Well major, I’m Signal Corps.”

At that, he just exploded

with a string of profanity. “I don’t need any Signal Corps officers. I need

Infantry officers.”

I could have assured him

that I had received lots of Infantry training and could handle the job of an

advisor... But I didn’t.

I said, “Major, someone made a mistake. I’m going to

go back to officer assignments and tell them you need an Infantry officer.” And

with that, we hung up.

My task now was to find a

job. A safe job. I went into the headquarters building of

MACV (Military Assistance Command, Vietnam) and walked up to the first sergeant I saw sitting at a desk. I said

to him, “Sergeant, I’m new in country. I have a degree in Electrical

Engineering, and I know some computer programming. Is there some group here that

could use me?”

Here's a picture of MACV HQ in Saigon.

He said, “I don’t know, sir, but go down the hall and talk to sergeant xxx and maybe he can help you.”

I was referred several

times, but I finally got to a place where they did computer programming. A

captain interviewed me and agreed to put in a request to officer assignments for

me to be assigned to his group.

I went back to office

assignments and talked to one of the assignments people, telling him that the

major didn’t want me but there was a group here at HQ that did want me. He cut

me orders to report to the computer group.

That turned out to be a

wonderful assignment. I worked in an air-conditioned office with clean and

pressed fatigues, and I learned a lot about mainframe computers. I worked

in

assembly language, and a bit of

COBOL. Here's a picture of the building where I worked -

on the second floor.

The reality of the office was that most of the programming was done by civilian contractors (Control Data Corporation had the contract). It would not have worked to have military people do the job. The military people were only there for a year and finding military people with the right experience, and teaching them the systems, would have been almost impossible. Even if you could find the right military people, they wouldn't stay long enough.

I did some work on the systems supported there,

but it took some effort. The civilian people were not very

willing to teach us military people much about internals of the systems. They viewed

their knowledge and expertise as job security.

We had some problems with the systems, but they were mainly in the data gathering area. For example, data for the Hamlet Evaluation System (HES) was gathered from Americans. The problem was that a middle-rank officer, such as a major, would have responsibility for an area, and lower grade officers, such as lieutenants, were responsible for the individual hamlets. The major was almost certainly a lifer (making a career of the military) and anxious to show progress so that he could get promoted . The lieutenants were most likely just in for the war and would leave the military at the first opportunity. The major would put pressure on the lieutenants to improve the hamlets, which generally couldn't be done. But with all that pressure, they would "improve" the hamlets on paper - the paper they submitted as part of HES. The output of HES was often not what the situation was "on the ground".

Even with that, I was able

to do a lot of computer work. I mostly taught myself and I stayed busy. There

was always more to learn and I was eager to learn it. It was great experience

that prepared me for a civilian job.

The two major software systems the contract programmers worked on were the Hamlet Evaluation System (HES) (also see here for the problems of the system) and the Terrorist Incident Reporting System (TIRS) (I couldn't find any reference that adequately describes TIRS). It was all programmed in COBOL.

For quarters, I was first

assigned to a BOQ (Bachelor Officer’s Quarters) on Plantation Road (Plantation

Road was the American name for the road – it was

Nguyên Văn Thoai Street back then and is Lý

Thuòng Kiêt

today). The buildings on that road were built next to each other with a shared

wall. The BOQ was just one of those buildings.

Next door to the BOQ was a

bar, and all the bars in Saigon had “tea girls” who would also spend the night,

on the second floor, with you for a fee. I used to watch young Vietnamese men on

motorbikes stop on the street in front of the bar at closing time. The girls

would go out to the men and either get on the back of the motorbike and leave, or

talk to the man and then go back into the bar. If she went back into the bar, it

meant she had a client for the night.

That may be difficult for

Americans to accept, but Vietnam was poor, and the woman could bring in a

significant amount of money that way. The poorest GI was fabulously wealthy

compared to the average Vietnamese peasant.

A story related to this - A GI based in Saigon might meet a Vietnamese woman and fall in love. She would talk him into renting an apartment and furnishing it, including with good quality stereo and camera equipment, which the GI could purchase at the PX. For a while, everything would be great. She'd have dinner ready when he came home from work, etc. But one day, he'd come home and the apartment was completely bare. His girlfriend, and her friends, had taken everything.

But the opposite also happened. One day, the GI didn't come home. His tour was up and he had gone back to the US.

There were a lot of

refugees in Saigon. They built small shacks wherever they could and tapped into

the power lines (power was distributed as 220 volts). But they had nothing else

– no water or sewerage.

Eventually, I was able to

move to a better BOQ, the Massachusetts BOQ, just outside the MACV compound. The

Mass was a big BOQ, with an officer’s mess on the top floor, and it showed

movies every night. I saw “Patton” there.

For being in a war zone, I received an extra $65 per month as hazardous duty pay. I was really in a safe situation, and felt bad about taking that extra money, so I sent the $65 home to my parents each month. That doesn't sound like a lot of money today, but back then it was a decent amount of money when a weeks worth of groceries was about $20.

I met my first wife in the

office. Norma Ferry was working for CDC as a secretary to the Lt. Colonel in

charge of the place. Norma was living in a “villa” at 40 Hô Biêu

Chánh Street in Saigon (just off of Cách Mang Street, now known as Nguyên

Văn Trôi) and I eventually moved in with her. Of course, I was supposed to be

living in the Massachusetts BOQ) but you can get away with a lot as an officer

in a war zone. A picture of Norma from one of her ID cards.

I was in Saigon at New

Years (1970 to ’71) and Norma and I went to a USAID party. At midnight most of the people

went up to the roof and watched the New Year come in. Every GI who had tracer

ammunition must have fired their weapon into the air at midnight. All around

Saigon the sky was lit up with tracers. Then the bullets started coming back

down to earth and one person on the roof was hit by a falling bullet (not

seriously injured). That got

everyone off the roof.

Norma had a Vietnamese

woman friend who was dating an Australian guy. They were going to take a

vacation to

Long Hai, which is across the bay from

Vũng Tàu, and they invited us

to go with them. It was interesting. The hotel was very basic - they only turned

the water on at certain times of the day - but it had a salt pool

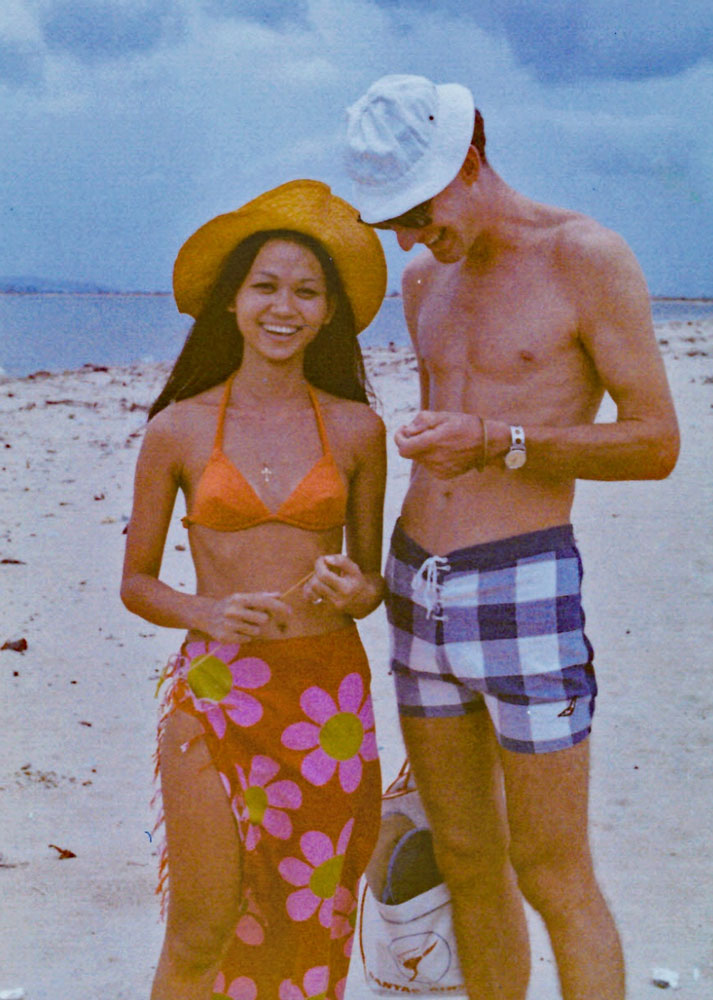

and they served drinks at the pool. Here's a picture of the Vietnamese woman and

her Australian guy. I wonder what happened with them.

There were some GI’s fishing just off the shore in a rubber raft. They had hand grenades, and they’d toss a hand grenade into the water to stun the fish. Other than making some big splashes, I never saw them catch any fish.

One night late when we were

home on Hô Biêu

Chánh, we were in bed when I heard an American voice crying “Help, please help

me!” I got dressed and took my Army .45 and went out on the street. Another GI

was out there and together we went down the street, each covering one side of

the street.

There was a GI who had been

shot in the stomach on the street. Someone else had called Third Field Hospital

and an ambulance was on the way. The other guy and I left because we didn’t want

to be caught “out” after curfew.

We learned the story later.

There was a bar on Hô Biêu

Chánh but it was single story, so the girls had to use some of the buildings

around the bar for their “clients”. Apparently, one of the girls had stolen the

GI’s wallet and money and he wanted it back. But Mama San had guards and one of

them shot the GI when he wouldn’t give up trying to find the girl.

As far as I know, he

survived, but I doubt if he got a Purple Heart.

One final picture - I received the Joint Services Commendation Medal for my work in Vietnam. Here's General Forrester pinning it on me. It's really fairly meaningless. Just about every officer who served in Vietnam got some kind of decoration. Note the MACV patch on my left shoulder. The general has a 1st Cavalry patch on his right shoulder, indicating that he served in the 1st Cavalry earlier in his career. He has a MACV patch on his left shoulder, indicating that he's with MACV in this assignment.

After I had been a second lieutenant for a year, I was promoted to first lieutenant. It was an automatic promotion - all second lieutenants got promoted after one year.

Living in Saigon during the

war was interesting and I have many, many stories about life during that time.

But I realize very few people are interested. For example, my family has never

asked me about my time in Vietnam. The only people who show any interest are

other veterans. We swap stories about our experiences, mostly the funny events.

The Army had a policy that

if an enlisted man returned to the US with less than five months left on his

obligation, he could be discharged immediately. For an officer, it was 90 days.

I did careful calculations and put in a request to extend my tour of duty in

Vietnam such that I’d return to the US with 89 days left on my obligation. (I

left Vietnam with 88 days left, but crossing the International Date Line going

east decreases the date by one day. I wanted to be very sure.)

To leave Vietnam, you have

to go through some clearance. First, you had to return your rifle. They didn’t

care about all the other things they had issued to you, but they were really

picky about any weapons.

Second, you had to pass a

drug test. Anyone who failed the drug test had to go through rehab “in country”

before you could leave. I didn’t have any problem with either of these

requirements.

I departed Vietnam on

August 2, 1971 in a chartered Boeing 707 from

Tân Son Nhut airbase (which was

next to MACV HQ). When the plane became airborne there was some clapping and

cheering, but it wasn’t that much. I suspect most departure flights were

similar.

I don’t remember much about

the flight home – whether we stopped for fuel or not. I know we landed at

Travis

Air Force Base and were bused to the

Oakland Army Depot for out processing. It

didn’t take a long time. They ran medical checks on us to show that we were in

good physical condition – I suspect so we couldn’t come back and claim we were

disabled. My DD-214 says that I was discharged on August 6, 1971.

They gave me my DD-214 and

a plane ticket home. I caught a ride to the San Francisco airport and a flight

to New Orleans. Although San Francisco was a hotbed of protest against the war,

I never encountered anyone who showed any interest in me, although I had my

military uniform on. See this

link.

That was the end of my

military service, and I never looked back. I got a job as a systems programmer

for a large IBM computer installation and built from there. The only thing I

regretted was that I lost three years of working and developing my career. The

people who had not served had three years of work experience now and had

probably been promoted in their jobs. I was just getting started.

I eventually got back to

communications and worked for AT&T and Rockwell Semiconductor. I hold 32 United

States patents, mostly on communication techniques.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Epilog:

Let me add something about the war. It’s impossible to win a war on the

defensive – you have to take the fight to the enemy. So why did we never invade

North Vietnam?

We let North Vietnam train and equip their soldiers with little interference or fear. They could then bring the equipment and soldiers down through Laos and Cambodia and choose the time and place for their attack. The US and ARVN soldiers could only react to those attacks. If we defeated the attack, they could retreat back to Laos or Cambodia to recover and refit.

You simply cannot win a war that way.

The reason we never went into North Vietnam is because of Korea. China made it clear that if we invaded North Vietnam, they would enter the war as they had done in Korea, and no US politician wanted another war with China on the Asian mainland.

So, we just kept reacting to the North Vietnamese attacks, until the American public refused to accept the number of American soldiers killed there.

Added note: I think the US has proven that you can't give democracy to other people - our Middle East adventures should have settled that. They either want it and fight to obtain it, or it doesn't happen. The North Vietnamese wanted to unify Vietnam and fought for it. In South Vietnam, we tried to do the fighting for the South Vietnamese. Not long after we pulled out, South Vietnam fell.

The government of South Vietnam was corrupt. Everyone who was in Saigon and had anything to do with the government knew that.

Perhaps the most disturbing revelation since the war was that LBJ knew there was no way to win in Vietnam, but he escalated our involvement in order to win the next presidential election. The book "The Vietnam War: A Military History" covers this very well.

Return to the Vietnam blog here