Antarctica

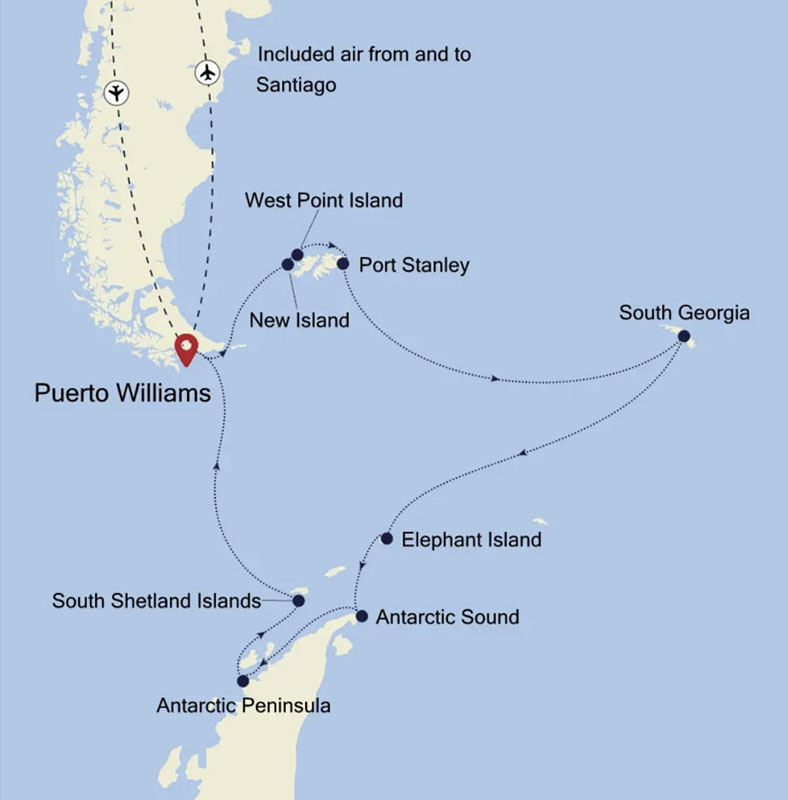

December 21, 2025 to January 8, 2026

Mike and Judy Henderson

We just arrived at South Georgia Island as I write this. Whenever people go to Antarctica they encounter stories about the Shackleton Expedition. I want to discuss the Shackleton Expedition in this blog but I had a question of where to introduce it - either here or when we arrive at Elephant Island. I've decided to do it here.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

12/27/2025 (Saturday) - We went to Antarctica in 2021/22 and for that trip I researched the Shackleton Expedition of 1914-1917 and wrote up what I had found. Since we're going back to Antarctica, I did more research and found additional pictures of the expedition. I'll post some of the Shackleton story here.

Ernest Shackleton was an experienced Antarctica explorer, having led the successful Nimrod Expedition of 1907-1909 to Antarctica. His ambition was to be the first to the South Pole, but Roald Amundsen got there first with his 1911 South Pole Expedition. (Robert Scott, with the Terra Nova Expedition, got there 34 days after Amundsen but the five men who made it to the pole perished on the return).

Shackleton was driven by the desire for fame and, while denied the fame of being the first to the pole, came up with the idea of being the first to cross the Antarctic continent by way of the South Pole.

This required a very extensive expedition, with two ships, each one on opposite sides of the continent. Shackleton could carry enough supplies to make it to the pole, but the crew of the second ship (the Aurora) would have to lay in supplies along the route from the pole to the terminus of Shackleton's trek, the Ross Sea.

Shackleton was able to acquire two ships, the Endurance for himself at the Weddell Sea side of the continent and the Aurora for the other side, at the Ross Sea.

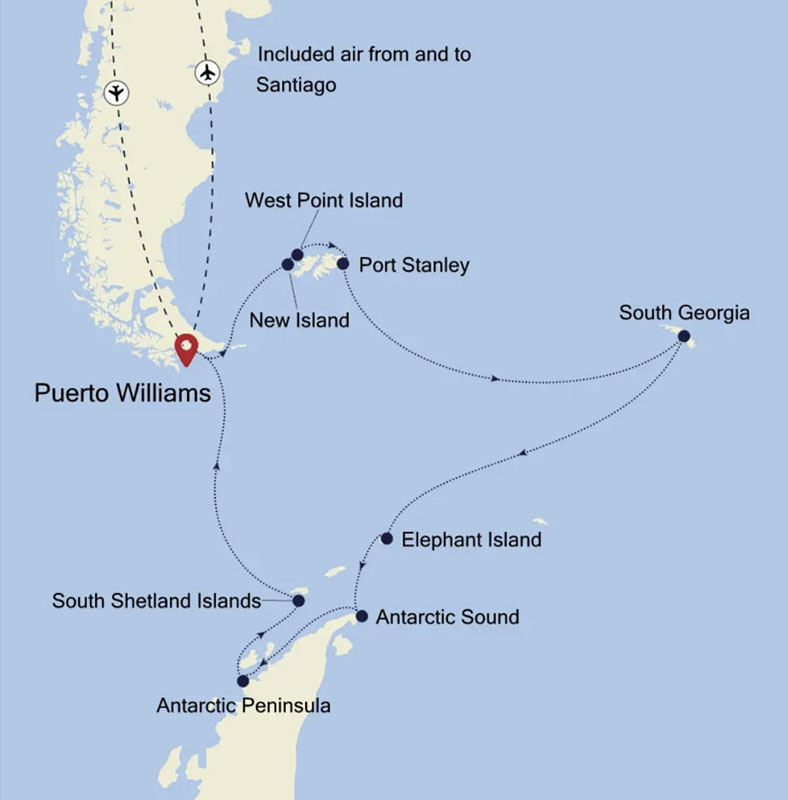

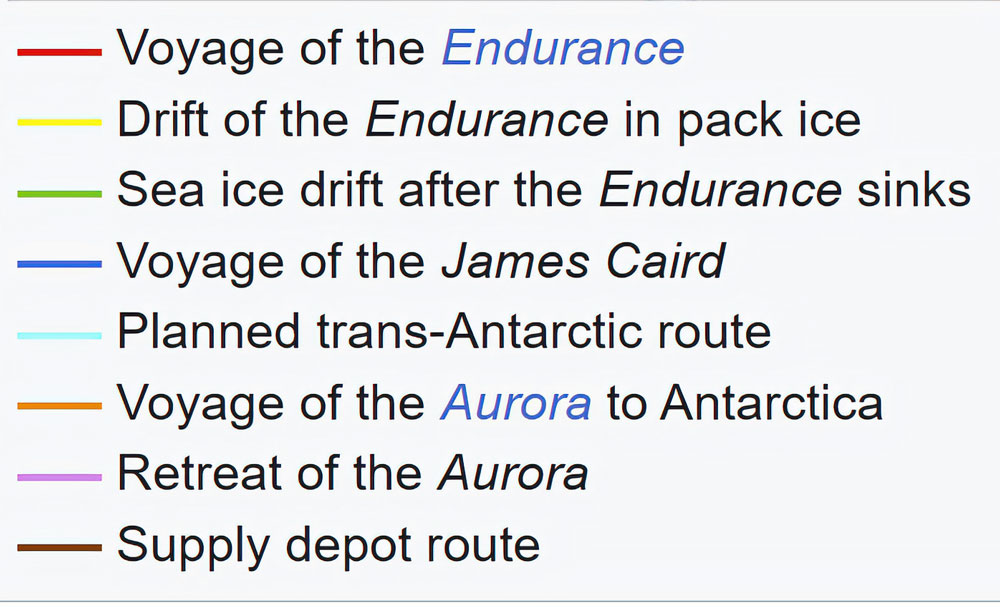

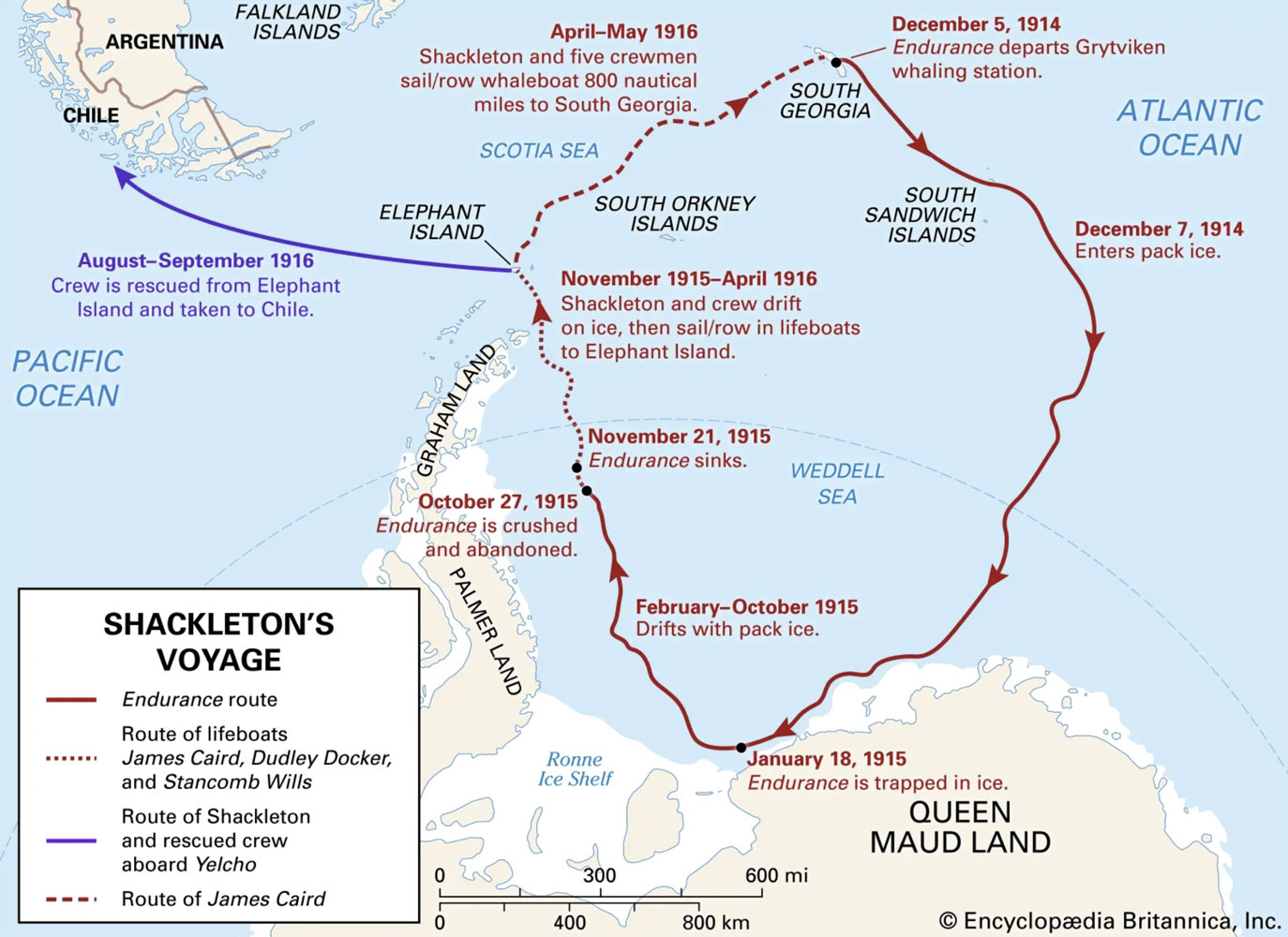

Here's a map of the full expedition, and the fate of the two parties. The legend is in French but I've included a translation which is very close.

The story of the expedition has always focused on the portion of the expedition led by Shackleton, but the crew of the Aurora, especially the shore party, suffered conditions as bad as the Endurance crew. There's a book about the Aurora crew, "The Lost Men: The Harrowing Saga of Shackleton's Ross Sea Party". Unfortunately, the book is not very good. The author goes into way too much detail about the planning for the trip, the hiring of a crew, the life story of each crew member, etc., rather than focusing on the voyage and the challenges the Ross Sea Party encountered in trying to place the caches of supplies. Shackleton never even started the cross continent trek, but the Aurora party could not know that, and worked diligently and faithfully under terrible conditions to lay in the supplies for someone who was never going to arrive. The Aurora party lost three men, and the other members of the shore party suffered terribly during that time.

There were 28 men in each party.

Here's a photograph of part of the Ross Sea Party. Some of the men in this picture are identified at the Ross Sea Party link.

But back to the Endurance Party. Shackleton hired a professional photographer, Frank Hurley, to accompany the expedition and he produced some amazing photographs of the expedition. I'll put some of his pictures here.

Here are the men of the Endurance party (really excellent picture, especially considering when it was taken and under polar conditions). There are 27 men in the picture. The photographer, Frank Hurley, is not in the picture. Here's a link to the names of the members of the expedition, both the Endurance Sea party and the Ross Sea party.

While the Endurance sailed from England, I'll pick up the story at South Georgia Island. The Endurance stopped in Buenos Aires on the way to Grytviken on South Georgia Island, arriving at Grytviken on November 5, 1914 (Grytviken was named by the members of the Swedish Antarctic Expedition in 1902 and means "Pot Bay"). Incidentally, Perce Blackborrow stowed away on the ship in Buenos Aires. They left Grytviken on December 5, 1914 and headed to the Weddell Sea.

There was an exceptional amount of ice in the Weddell Sea that year, and on January 18, 1915, the Endurance was trapped in the ice.

I'm getting a bit ahead of myself, but here's a map of the path taken by the Endurance and the Shackelton Expedition, along with important dates.

The ice in the Weddell Sea is not fixed, but rotates in a clockwise direction due to the Antarctic Circumpolar Current flowing from west to east through the Drake Passage. This meant that the Endurance was carried along with the ice, more or less in a northerly direction from the place where it was trapped.

The crew of the Endurance was well provisioned since they planned to support an attempt to cross the continent, so being trapped was not a disaster. They resigned themselves to spending the year trapped in the ice, to be freed with the coming of spring (remember they were in the southern hemisphere so their spring would be September/November).

They made igloo kennels for the sled dogs and unloaded the dogs to the ice. Here's Samson, the biggest dog, in his igloo kennel.

Life settled down to a routine. They hunted seals and penguins for food, especially for the dogs. Here the crew is playing some sport on the ice.

The camp area, with the dogs.

With the coming of winter, it became dark almost all day, every day.

Hurley documented their life in photographs during that time - I included some links to them later in this blog. While not about the crew, he produced the most iconic photograph of the expedition, a picture of the Endurance in the dark, illuminated by Hurley with flares.

Here's a note from Hurley's diary about the picture:

"During the night take flashlight of ship beset by pressure. This necessitated

some 20 flashes, one behind each

salient pressure hummock, no less than 10

flashes being required to satisfactorily illuminate the ship herself.

Half

blinded after the successive flashes, I lost my bearings amidst hummocks,

bumping shins against projecting

ice points & stumbling into deep snow drifts."

- Frank Hurley, diary 27th August 1915.]

However, the ice began to pile up, perhaps pushed from the land as the ice rotated, and on October 27, 1915 the Endurance hull was crushed. The crew off-loaded everything of value and on November 21, 1915, the Endurance sank at approximately 68°44'21" S, 52°19'47" W.

Now things began to get desperate. The party was on the ice, the ice was rotating, and as it rotated it began to break up. If they didn't do anything, the ice they were on would eventually break into small pieces and they'd lose their supplies and possibly some of the crew.

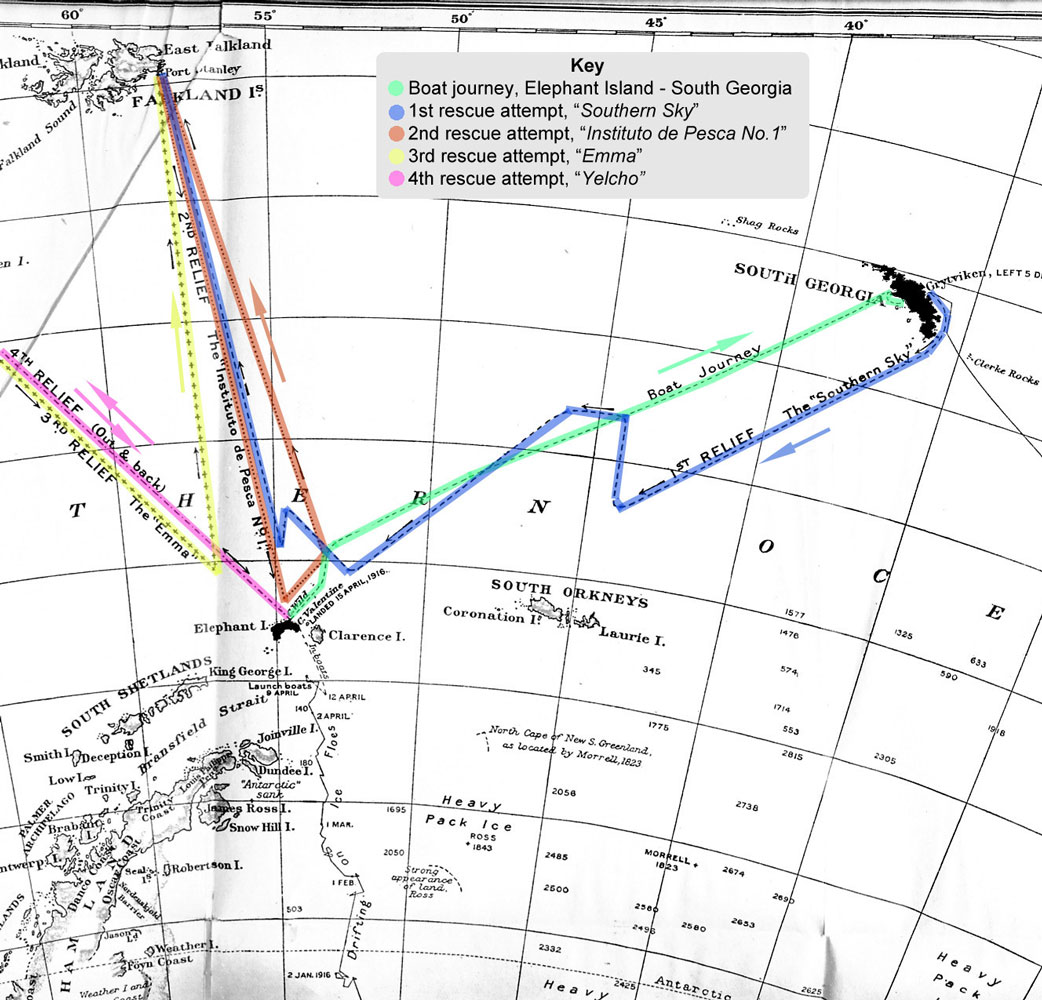

Shackleton decided it was time to take to the lifeboats - the James Caird, Dudley Docker and the Stancomb Wills. They left the ice floe on April 9, 1916. Elephant Island was about 100 nautical miles away and they arrived there on April 15, 1916.

Frank Hurley had to leave his professional cameras and some of the photographs he had taken because there was limited space in the lifeboats. All he had for photographs on Elephant Island was a hobby type camera and 38 exposures of film. Here's the camera he had. All the following photographs of their time on Elephant Island were taken with this camera.

They first landed at Cape Valentine but it was not a viable place for them, so the next day Frank Wild and some of the crew took the Stancomb Wills along the north, lee shore and found a spit of land that would be a safe place to camp. The whole party then moved to that location which they named Camp Wild, now called Point Wild.

Shackleton immediately recognized that they had to get help and arranged for the James Caird to be prepared for the 800 mile voyage to South Georgia Island. Here's a picture of the carpenter, Harry McNeish, working to raise the gunwales of the James Caird. He also covered a major portion of boat.

Shackleton would take the James Caird, with Frank Worsley (captain of the Endurance), Tom Crean (second officer), Harry McNeish (carpenter), Timothy McCarthy (able seaman), and John Vincent (able seaman), and attempt to sail to the Stromness whaling station at South Georgia Island. It was the nearest place they could attempt to reach where they could find help. The strong eastward current and winds in the Drake Passage would prevent them from making Tierra del Fuego or the Falkland Islands.

Hurley still had a camera and he documented the launch of the James Caird.

Here the remaining crew members are watching the lifeboat sail away.

They knew that if the boat didn't make it, their chances of survival were slight.

The last picture of the departing lifeboat.

They had a backup plan to attempt to sail to Deception Island where whalers occasionally called, but their two remaining boats were in poor condition and ill-suited to that journey.

Since there were six men in the lifeboat, that left 22 men on Elephant Island. Here's a group shot.

If you count, there are only 20 men in the picture. Hurley was taking the picture and Blackborrow was disabled by frozen toes.

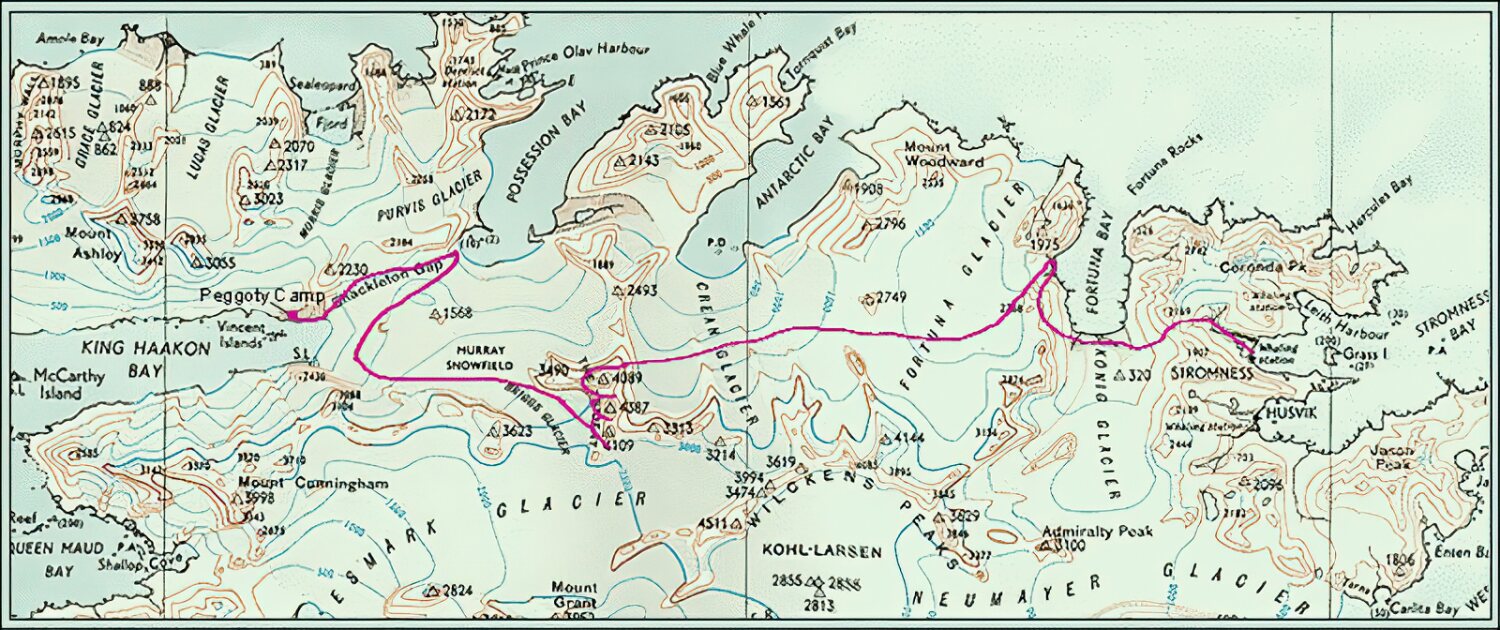

The journey was 780 miles in an open boat, to find a small island in the South Atlantic - but Shackleton and his crew made it, arriving at the uninhabited area of King Haakon Bay in South Georgia on May 10, 1916. (I encourage you to read the account of their voyage here. It's pretty amazing.) Their ordeal was not over, however, and Shackleton, with Worsley and Crean, set off on May 18, 1916 to cross the mountains of the island of South Georgia on foot, to reach the Stromness Whaling Station. They arrived at Stromness on May 20, 1916, 36 hours after departing their landing area.

Here's a more detailed description of their trek across the island. Here's another version of the trek.

The island of South Georgia had never been crossed before, was uncharted, and was not crossed again until 1955.

Shackleton immediately arranged for a ship to get his men at King Haakon Bay, and left Stromness within 72 hours (May 23, 1916) in the ship Southern Sky, to rescue his men, but was turned back by ice - see here, here, and here. He made three more attempts to rescue the men, two of which failed due to weather, ice and/or mechanical problems.

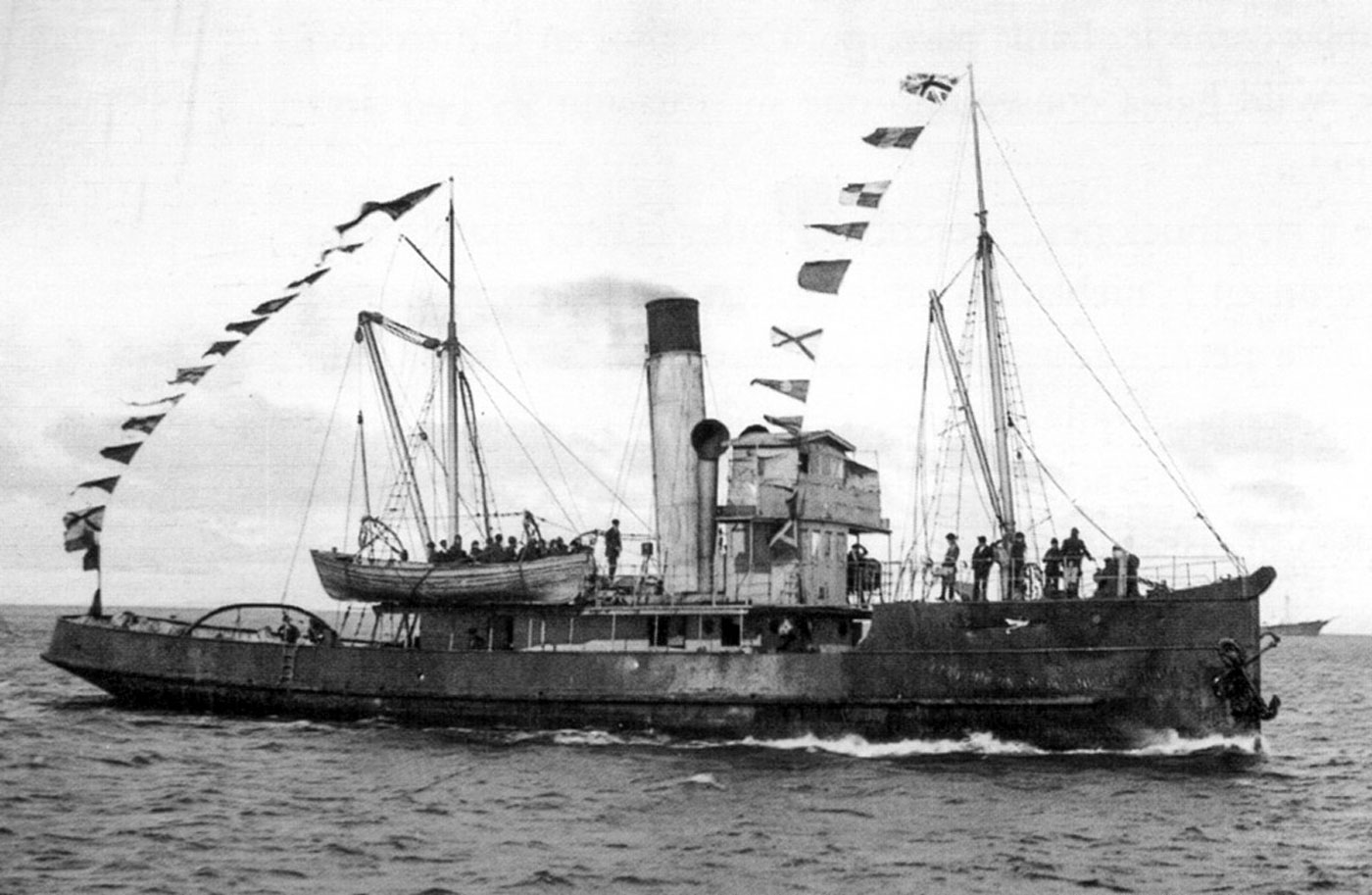

But on August 30, 1916, the middle of winter, slightly more than four months after leaving the men on Elephant Island on April 24, 1916, Shackleton returned on the Chilean sea-going tug, the Yelcho, captained by Luis Alberto Pardo Villalón.

All of the 22 men were still alive, although Perce Blackborrow had suffered frostbite on his toes and developed gangrene. Drs. Alexander Macklin and James McIlroy had successfully amputated his toes on the island. They used the last of the chloroform they had.

The camp was sighted on August 30, 1916. Note the signal fire at the far left in this picture and the Yelcho on the horizon.

Here's another picture of their rescue.

The men were taken to Punta Arenas where they were greeted and cheered by the people there. Here's a picture of Shackleton and crew in Puenta Arenas with local officials.

The expedition was well documented - Shackleton had included his professional photographer, Frank Hurley, on the voyage and Hurley produced many photographs, including of their time on the ice and at Point Wild. His photos are held by the Royal Geographic Society and can be seen here, here, here, and here, and in book form here. I highly encourage you to view the pictures - they are amazing, especially for the time. You can see some information about the equipment Hurley had here and about Hurley here. Over a hundred glass negatives, and his professional cameras, had to be left on the ice, because of weight, when they took to the boats, headed for Elephant Island. The pictures Hurley took on Elephant Island were with a basic, non-professional camera and the images are not as good as his earlier ones.

Most of the pictures taken by the Ross Sea party were lost.

In 1987 Chile placed a bust of Captain Luis Alberto Pardo Villalón on Point Wild of Elephant Island.

While he and his ship saved the men, his contribution to the rescue was very small compared to Shackleton's - but he was Chilean and Shackleton wasn't.

If you're interested in learning more, the best book about the expedition is "Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage" by Alfred Lansing. For a more personal account, you can read "South: The Story of Shackleton's 1914-1917 Expedition" by Shackleton. It's free in Kindle format. If you'd like the short version, click here (several web pages long). Many of the men kept diaries, and they were saved with the men. They were an invaluable source for those who wrote the story of the expedition.

Shackleton did not forget the Ross Sea Party. He went to New Zealand and joined the repaired Aurora which journeyed back to the Ross Sea and picked up the shore party on January 10, 1917.

The First World War was in progress and Shackleton and the crew's return to England did not generate a lot of news.

Shackleton did not give up on Antarctic exploring and organized another expedition, the Shackleton-Rowett Expedition on the ship Quest. The Quest departed London on September 17, 1921 for South Georgia Island. On January 5, 1922, Shackleton died of a heart attack on the Quest while docked at South Georgia Island. He was 47 years old. He's buried in the Grytviken cemetery.